Breathing in the ocean

Feb. 14, 2019

By Nate Smelle

While waiting out a freakishly intense snowstorm that grounded thousands of travellers overnight at the airport in Toronto on Jan. 28, I decided to indulge in a bit of research on the destination where I was headed: the Península de Ancón near Trinidad, Cuba.

With only a week to explore and a deep yearning for an oceanic experience, I decided to focus my attention on the marine life inhabiting the salty waters of the Caribbean Sea I would soon be immersed in. Browsing through countless photos and reports on the seemingly endless abundance of sea creatures inhabiting the south central coast of Cuba, I devoted my last two hours on the airport floor to re-watching biologist and filmmaker Rob Stewart's testament to the value of ocean life, Sharkwater.

Highlighting how life on earth evolved from the sea, Stewart explained how aquatic single-celled organisms gave rise to algae, coral and tiny planktonic animals, squids, mollusks, vertebrates and eventually a planet full of life. As the ocean's apex predator, he explained further how sharks have survived five major extinction events and acted as architects of evolution for 400 million years, by inspiring their prey to develop schooling behaviour, camouflage, speed, size and communication.

Making a case for why sharks are also an important element in the fight against human driven climate change, Stewart said “Sharks' presence in the ocean has provided a framework for the populations below them including phytoplankton – tiny aquatic plants that consume more carbon dioxide than anything else on earth. Carbon dioxide is a global warming gas, and plankton converts it into oxygen, providing 70 per cent of the oxygen we breathe on land. Without sharks to prey on them, plankton-feeders below sharks could grow out of control, consuming the plankton we depend on for survival.”

Despite our understanding of how vital sharks and sea life are to the ecological integrity that sustains all life on earth, Stewart's film also sadly acknowledged how long-line and trawl fishing are decimating shark populations and destroying marine ecosystems around the globe.

With almost perfect timing the film wrapped up as I heard the boarding call for the flight to Cienfuegos. Before long, I was standing in the lobby of the Amigo Ancon. Having already lost a day and a half of my trip to the weather, I arrived drooling with excitement to taste the salt of the sea on my tongue. After polishing off a pitcher of rum punch while waiting to check in, I dropped my bags off at the room and then went down to the beach for a quick swim beneath the setting sun.

Exhausted by the journey I nodded off early. Awakening the next morning before dawn, I roamed the shoreline as the sun climbed from the Escambray Mountain range to the east, walking until I found the dive shop. From that point on, with the exception of a few hours here and there at the bar and the buffet, I was underwater.

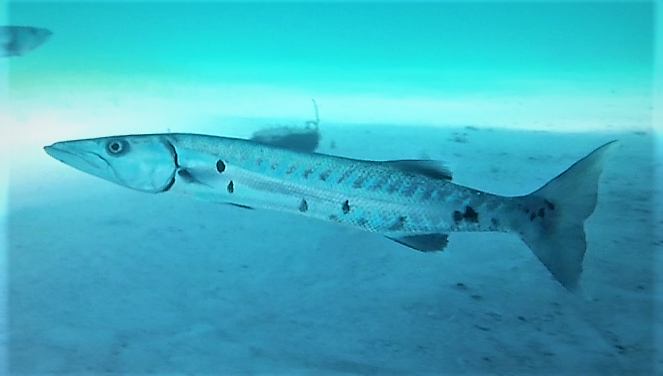

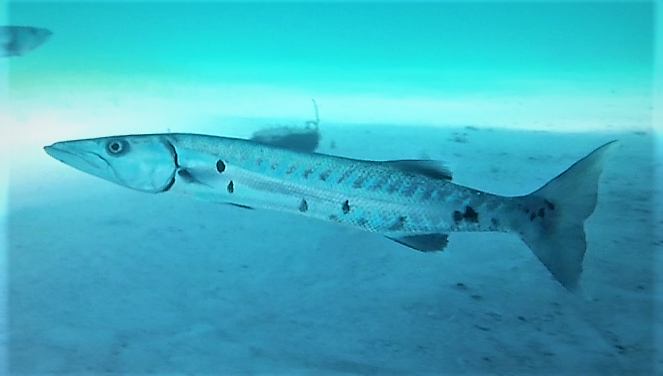

During my time submerged in the aquamarine environment, I swam face to face with several species, including a curious barracuda, a feisty green moray eel, a friendly pair of gray angelfish, a solitary red snapper, a shy lionfish, schools of yellowtails and blue tang at least 1,000 strong, and several parrotfish, banded butterflyfish, squirrelfish and pufferfish. Astounded by the rich biodiversity of the coral reef lining the coastline, I found myself sailing out to sea twice a day to drink in the life thriving only a kilometre from where I slept.

Getting to know my fellow divers a little better each day, I learned that one of the guides, Igor Jiménez, had been diving Cuba's south coast for some 30 years. Hoping to catch a glimpse of a sea turtle or a shark, I asked if he had ever seen either of these species in the area. Although he had crossed paths with them in the past, he said that over the last decade they have become more and more scarce due to illegal long-line and trawl fishing that takes place along the outer edge of the reef.

Using fishing lines up to 10 kilometres long that are baited with thousands of fishing hooks and left to drift for hours, long-lining is responsible for indiscriminately killing species with little to no commercial value such as seabirds, sea turtles, sharks and whales. Trawl fishing – the dragging of large nets (up to 100 metres wide at the mouth) along the sea bed at a speed faster than most fish can swim – also reels in a massive amount of bycatch, while at the same time ravaging seafloor habitats such as kelp forests and coral reefs that are fundamental in the functioning of marine ecosystems.

With Sharkwater still fresh in my memory as we sailed back to shore, it dawned on me how interconnected we are with these issues every time we take a breath. It also occurred to me how every one of us can make a difference each time we step into a grocery store. As Rob Stewart said “It is not just about saving sharks, it's about saving ourselves.”

|