General News

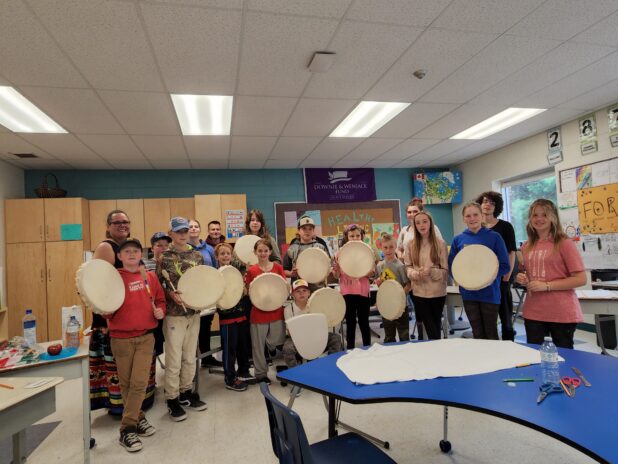

Drum making and drum awakening ceremony at Whitney PS

June 29, 2022

By Mike Riley

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

According to a Renfrew County District School Board Facebook posting on June 9, students at Whitney Public School in Whitney had the opportunity to make their own traditional Indigenous drums and have a Drum Awakening Ceremony, courtesy of the guidance and teachings of Trevor Pearce and Marsha Depotier. In addition to this, Pearce and Depotier gifted the class a beautiful blanket. Christine Luckasavitch, owner and executive consultant with Waaseyaa Consulting, Indigenous culture and heritage consultants, Whitney Public

School teacher Ashley Schutt and a couple of students from Scutt’s class comment on this fun and educational day for the students at Whitney Public School.

Schutt told Bancroft This Week that Whitney Public School is a legacy school of The Gord Downie and Chanie Wenjack fund. This fund aims to build cultural understanding and create a path toward reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples. By building awareness, education and connections between all peoples in Canada, their goal is to improve Indigenous peoples’ lives. The fund’s legacy school program is a free national initiative to engage, empower and connect students and educators to further reconciliation through awareness, education and action. You can find more information on this great program by visiting www.downiewenjack.ca, or by emailing staff@downiewenjack.ca.

Schutt says that Pearce has worked with the school and its students for years on Indigenous initiatives and that Holly Hayes, South Algonquin’s former CAO/clerk-treasurer, reached out to them at the beginning of the school year to see if they wanted to take part in the drum making classes.

Schutt says that Pearce has worked with the school and its students for years on Indigenous initiatives and that Holly Hayes, South Algonquin’s former CAO/clerk-treasurer, reached out to them at the beginning of the school year to see if they wanted to take part in the drum making classes.

Hayes said that prior to COVID-19, she was on the parent council and had been loosely trying to do some things as everyone transition out of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“A few months back, Jonathan [Pratt, the Whitney Public School principal} contacted me to explain a grant that was available to the school and wondered if I had any ideas. Last summer, I was fortunate to be invited to a KAIROS blanket ceremony that was hosted in my community and I met Trevor [Pearce] who was one of the hosts and we talked about drums that he had made with youth. Jonathan and I made a plan to ask Trevor and he brought his friend Marsha [Depotier} and they spent two days making a drum and blessing it. Our kids are so fortunate to have had this experience,” she says.

In Indigenous cultures, the drum signifies the universal heartbeat of Mother Earth, and Indigenous people manifest this heartbeat by playing a special rhythm on the drum, which brings about healing and realignment with the four realms of human existence; mental, spiritual, emotional and physical. The drum provides a constant reminder of the responsibility to preserve and ensure the good health of Mother Earth. The drum is the exclusive property of the person who made it.

The Drum Awakening Ceremony, once the drum has been made, is necessary to bring out each drum’s unique voice and vibration, and no drum should be played until this sacred ceremony is held.

According to Northern College (www.northernc.on.ca), during the ceremony, the drum is dedicated to the Creator, and as a sacred object, when it is not in use, it should be placed in a bag made of natural materials, animal hide side up as a sign of respect. Prayers are said each time the drum is used to give thanks to the Creator and ask that the Creator allow the user of the drum “to sing in a good way” as they’re playing.

Schutt teaches grades 4 to 8 and FSL at Whitney Public School and a couple of her students, who wished to remain anonymous, provided comments on their experience making the drums.

“The drum awakening ceremony went well and it was a really intriguing and spiritual experience. Trevor and Marsha came with their drums and played songs with us as well as helping us awaken the drums. The process had multiple steps, including letting the drums feast and drink with berries and water. Then, we put tobacco in the middle of the drum and when Marsha and Trevor came around the wake the spirits, the tobacco danced around the drum from them drumming. When they started to hit their drums with their strikers and the tobacco went to different places on the drums because they mean different things.”

“The making of the drums was fun. We made the drums with wooden frame, then we put the deer hide over the frame and tied it together with the deer hide. Trevor was doing the drum making and Marsha had her own way of doing it so it was cool how we got to experience two different ways. All the drums were different in the ways they curve the sounds and the feel of the drum. It’s really special how Trevor and Marsha made them with us.”

Luckasavitch is an Algonquin community member and worked for a time at the Algonquin Inodewiziwin EarlyON child and family centre (offered through North Hastings Children’s Services) in Bancroft and is an alumnus of North Hastings High School. She says that she was not involved with the drum making class in Whitney, but has known Pearce and Depotier for years and is impressed with all the positive work that they do, along with their colleague Heather Taylor, teaching Indigenous culture to young people.

“I’m really inspired by the work they do for Indigenous kids as well as teaching the whole community about Algonquin culture. I really wish I’d have had those supports when I was a kid. It’s incredible to see and it’s incredible that they offer that support to all Indigenous students,” she says.

Luckasavitch says that while there’s a large Indigenous population in Whitney and Bancroft, there’s been a disconnect from those cultures, so bringing these teachings back is more remarkable than anyone realizes.

“It’s helping to create a better understanding of Algonquin and other Indigenous peoples that now call this place home, that we’re still here and that we’ve always been here. But also, there’s something to be said about, through education and all those learning opportunities, they’re dismantling stereotypes. So, there’s lots of work being done by Indigenous folks right now across the world, where we have an opportunity to tell our own stories and to share our own culture,” she says. “We weren’t able to do that for a long time so that’s why things like this are so significant to happen.”