Headline News

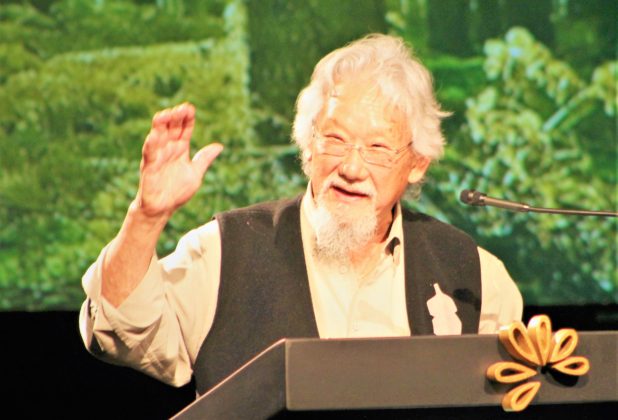

Learning from COVID-19 and solving the climate crisis with Dr. David Suzuki

April 20, 2020

April 20, 2020

By Nate Smelle

Last Thursday evening The Bancroft Times celebrated Earth Day early by participating in a Zoom call with environmentalist Dr. David Suzuki and some 350 people from across Canada and the United States. Hosted by the National Observer’s CEO and editor-in-chief, Linda Solomon, the hour-long conference call focused on opportunities arising from the COVID-19 pandemic that could help humanity deal with the climate crisis, and nurture a more habitable planet for current and future generations.

Suzuki made the call from a cabin on Quadra Island where he has been staying with his family since B.C.’s province-wide lockdown came into effect on March 26. Although stuck on the island with only three pairs of knickers, he has been making the most of the time with his family, marvelling at the wonders of nature all around them. In this relatively short period of time, Suzuki said they have witnessed massive migrations of geese filling the skies, a pod of orcas swimming in the gulf, and during the call that night, a school of salmon feeding in the stream outside their cabin window. From these experiences, he said he has “the sense Mother Earth is saying ‘Phew!’ Thank God these busy people are giving me a break!”

Because of the global slow-down and the ensuing reduction in greenhouse gases and pollutants entering the atmosphere at the moment, Suzuki said he is hopeful that people living in major urban centres like Beijing or Bombay will come to appreciate what it is like breathing air when it is the way it should be, “invisible and odourless.” Elaborating on his feeling of hopefulness, Suzuki said “I would like to think that this is the end of the way we have been going since the end of World War Two … We have been living it up like there is no tomorrow. Well, now we better start thinking of about it because tomorrow is coming, and it is not looking very good.”

Reflecting on the “war metaphor” being used to describe the level of civic engagement necessary to fight the pandemic, Suzuki said the same degree of public participation and political will is needed to overcome the climate crisis. Rather than bailing out the oil companies in Canada’s “tar sands” in response to the impact COVID-19 is having on the fossil fuel industry, he said the government would better serve the people, country, and the planet by directly supporting the workers in this sector. Instead of using their knowledge to extract more fossil fuels and increase GHG emissions, the talents of these individuals would be better utilized in the fight against climate change, he said.

Providing an example of one opportunity to reemploy these individuals, Suzuki said “In Alberta we have all these orphaned wells, and they are leaking methane gas into the atmosphere. Recruit people with the skills from the tar sands to begin to plug these. Get society working on re-wilding the planet; and, to create a liveable place for us. The job opportunities will be immense!”

Suzuki explained that one of the biggest obstacles standing in the way of positive and necessary change is the economic system itself. One of two “fundamental problems” with the economic system, he said, is that it devalues life-giving ecosystem services produced by nature – the cleansing of water, creation of soil and food, generation of breathable oxygen to name a few – identifying them as “externalities” not to be factored into the economic equation. The other main issue with this system, Suzuki said, is that it relies on the concept of endless, unfettered economic growth.

“We have bought into the idea that the economy must grow forever,” said Suzuki.

“Now that’s the creed of cancer cells – endless growth. We have constructed an economic system built on the creed of cancer in which we ignore the fundamental things that keep us alive. If that isn’t a screwed up system, I can’t think of one. We better turn that out and change it. It’s a human construct. It’s not a force of nature, so let’s change the thing to make some sense.”

In order to create a system that does make sense, Suzuki said “We have to live in a different way. We have to depend much more on ourselves, and localize food, localize services, localize industry. That has got to be the way we go – much more self-sufficient.”

Acknowledging the hardships people are now facing as a result of COVID-19, Suzuki empathizes with the struggles of single parents shut in tiny apartments, elders in elder care homes, and front line workers. As difficult as life has become for so many people due to the pandemic, he said it appears to be giving people a chance to discover a sense of community.

Suzuki sees the current situation with the pandemic as a “huge opportunity” to shift society towards a better and more sustainable way of life. Considering how focused people have become on the fight against COVID-19, he pointed out how there is much to be learned from this moment in time.

“Look at what the government is doing with this crisis,” Suzuki said.

“They are doing things that were inconceivable six months ago. Look at the money they are putting into it. If they would have put a fraction of that money and effort into dealing with climate change, we wouldn’t be in the crisis we are in there.”

Drawing attention to the fact that many Indigenous communities already have a very limited supply of resources in terms of health care, Suzuki expressed great concern for their health and safety should a major outbreak of COVID-19 occur in such a community. Since many of these communities exist in isolated areas, he said if the virus were to spread throughout one of these communities they would not be able to evacuate everyone who needed critical care.

“I have two Haida grandsons and they are on Haida Gwaii right now,” said Suzuki.

“I know that their grandparents are absolutely terrified because of course their Elders tell stories of the great small pox epidemic that wiped out 90 per cent of Haida in two years. Can you imagine such a catastrophe? It’s a miracle they survived. They are trying to lockdown the island completely, but I know that there are contaminants that have already entered Haida Gwaii. For Indigenous communities there is that collective memory of what the first encounter with Europeans did to them in terms of disease … It’s a very terrifying situation for Indigenous communities.”