General News

Over the Hills of Home: remembering poet Lilian Leveridge

April 28, 2022

By Mike Riley

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

For National Poetry month in April, Bancroft this Week wanted to take a closer look at a local award-winning poet named Lilian Leveridge to celebrate the occasion. Leveridge lived on a farm near Coe Hill in her younger years, but was born in England. We take a look at her life and poetry, with comments on her work from McGill University English professor and author Eli MacLaren and Algonquin College English professor and author Michele Hall.

Leveridge was born near the village of Hockering in England in 1879, but came to Canada at four years old with her family; which included her parents, Anna and David and her six siblings. In addition to writing poetry and short stories, she taught school in Manitoba and Ontario and worked as a stenographer in Toronto. Her poem “The Whitethroat” received an honourable mention in the 1937 Montreal Poetry Yearbook Competition for the Best Bird Poem, sponsored by the Canadian Authors’ Association. In 1945, she took second and fourth place in the McNab Poetry Award, for her poems Glamoresque and Open Gate respectively. Sustaining an injury after slipping on ice in 1950, and unable to walk afterwards, Leveridge sadly passed away three years later at the age of 74 years in Carrying Place, Ontario.

In the book Over the Fields of Home: Selected Poems of Lilian Leveridge and World War One Diaries and Letters of Frank Leveridge, published by Paul Kirby of Kirby Books, Leveridge remembers how the scent of English violets always reminded her of her birthplace, England.

“In fact, a whiff of violets is really all my memory of my native land amounts to,” she said in the book.

With scant financial prospects in England, Leveridge’s father went off to Canada alone to find work, subsequently sending for his wife and children, including little Lilian, a year later. According to Leveridge, they lived for a year in Millbridge in what is nowTudor and Cashel Township, and then her father bought a farm with acreage north of Coe Hill, and they settled permanently in what Leveridge called a “veritable wilderness.”

Leveridge’s mother, having been a schoolteacher and church organist before she married, took on the education of Lilian and her siblings, instilling in them a love of knowledge with her lessons, as well as a love of reading and a feel for poetry, music and art.

Leveridge’s mother encouraged her children to use their imaginations and create their own fun by learning and inventing games, telling stories and reading aloud, which they readily enjoyed doing.

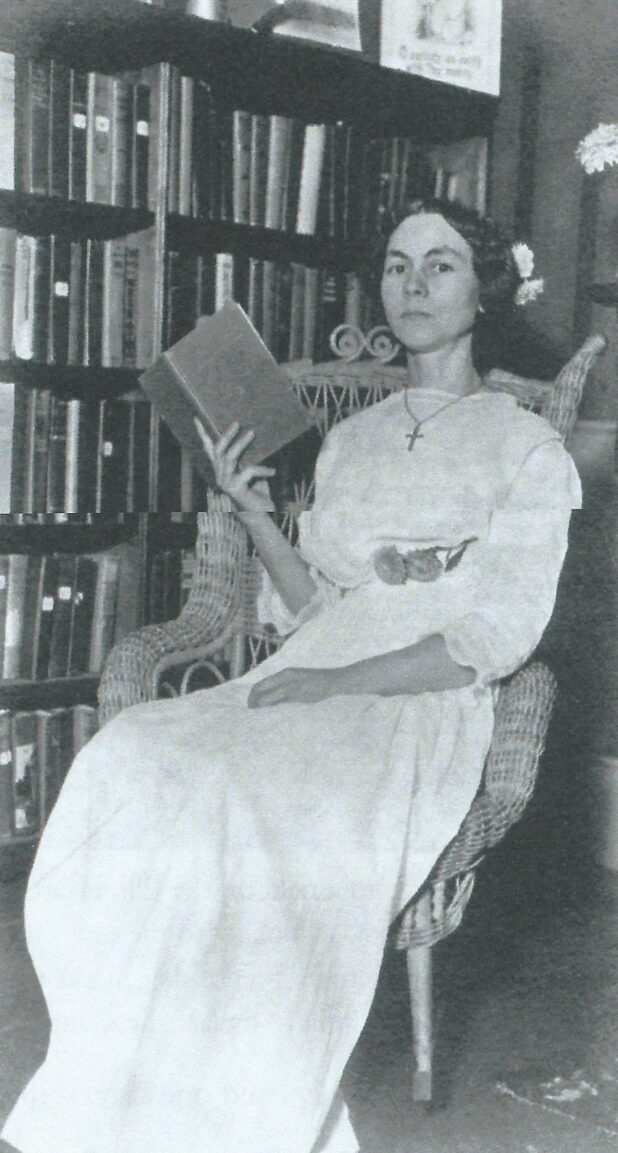

W.D. Hanthorn, Lilian’s nephew, wrote in Gunshot and Gleanings of the Historic Carrying Place, Bay of Quinte, that everyone who knew Leveridge loved her. He revealed that his aunt loved nature and would roam the countryside in her spare time. She was an avid reader, and he says she inherited her love of writing poetry from her mother, who encouraged her in her poetic pursuits.

Hawthorn recalls he visited her in Toronto while he was attending mechanics’ school, and said she lived frugally by typing manuscripts for other writers.

“She served others all her life, finally retiring on an annuity of $15 a month to live with her sister Gertrude in Carrying Place. Here, she played the church organ every Sunday, walking to and fro, rain or shine,” he says.

Richard Trounce, whose grandmother was Leveridge’s older sister, recalled in Over the Fields of Home: Selected Poems of Lilian Leveridge and World War One Diaries and Letters of Frank Leveridge, that he paid family visits to Leveridge at her sister’s house in the 1940s and early 1950s and he said at that point she was still writing poetry and for various publications.

“In her daily life, [Leveridge] was a very private person, but in her poetry, she revealed her innermost thoughts and feelings to the world. She chose subjects that she was familiar with and she liked. She also used her personal experiences and her love of nature to paint powerful word pictures,” he says.

Perhaps Leveridge’s most famous poem was a tribute to her brother Frank, who died fighting in the First World War, called Over the Hills of Home. Published in 1918, this was a poem which the August 1919 edition of the Daily Ontario newspaper said “contributed to the wealth of colonial literature with a heart song that girdled the globe.”

Hawthorn said that Leveridge struggled hard for recognition, publishing books of poetry at her own expense, and that she had many literary friends including Pauline Johnson. He says that whenever he hears the Beautitudes [the blessedness of those who have certain qualities or experiences peculiar to those belonging to Heaven] chanted in church, he often thinks of her, and feels that she would have fit into every category.

MacLaren says that Leveridge’s poetry practiced a metrical, rhyming style modelled by the Confederation Poets a generation earlier, and that she particularly looked up to Bliss Carman, thought of as “the unofficial poet laureate of Canada” by his peers. In addition to Carman, the Confederation Poets included Charles G.D. Roberts, Duncan Campbell Scott, William Wilfred Campbell and Archibald Lampman. Later on, according to Poetspathway.ca, poets like Pauline Johnson, who was a friend of Leveridge, would also be included in this list.

The Confederation Poets were a group of Canadian poets born in the 1860s, the decade of Canada’s Confederation in 1867. They rose to prominence in the late 1880s and 1890s. However, they were not known by this moniker at the time. They were named this by Malcolm Ross, a Canadian professor and literary critic, in the introduction to his 1960 anthology Poets of the Confederation.

However, MacLaren believes Leveridge wasn’t well placed to spearhead a new movement in poetry, and for this reason literary history has passed over her in favour of the innovators, such as A.J.M. Smith.

“But she was a talented and dedicated poet. Lorne Pierce, editor at the Ryerson Press in Toronto, supported her by helping her publish several slim collections,” he says.

These collections were; A Breath of Woods in 1926, The Blossom Trail in 1932 and Lyrics and Sonnets in 1939. The Ryerson Poetry Chapbooks were a poetry series that lasted from 1925 to 1962. In addition to Leveridge, the series showcased titles from 200 writers from across Canada, half of them women.

MacLaren says he admires Leveridge’s poem A Breath of the Woods, from her collection of the same name in 1926.

“It conceives of poetry through this metaphor. That is, she holds poetry to be a breeze stirring in the forest, a fresh inspiration capable of trof tiresome pressures,” he says.

Hall, also a fan of Leveridge’s poetry, discovered her while studying the book designs of the Ryerson chapbooks, known for their delicate, ornate illumination. One of these chapbooks is Leveridge’s A Breath in the Woods, number 18 in the series and has some stunning, art-nouveau style woodcut embellishments.

“While I was drawn to the book for its design, I was moved by the beauty of Leveridge’s lyric, pastoral poems. I also admired her unique voice as a woman struggling with loss, and trying to find her place in a fast-changing world,” she says.

Hall says that Leveridge was writing in an era of transition in poetry in general, with Ezra Pound calling on poets to reject the measured, formal, genteel or feminine verse of the day and embrace a more dynamic, imaginative and virile style of poetry. Hall says that the literary environment of the early 20th century was hostile towards women writers and femininity in general, as elucidated in No Man’s Land: The Place of the Woman Writer in the Twentieth Century by Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar. She also reveals that in Canada, early scholarship of 20th century Canadian poetry was dominated by male poet-scholars like E.J. Pratt, F.R. Scott, Louis Dudek, Irving Layton and others, who tended to model masculine modernist ideals in their own poetry and prioritize them through their public discourse and academic teaching and research.

“Until recently, the diverse voices and varied aesthetics of Canada’s so-called “minor poets,” including Leveridge, have been overlooked and undervalued by scholars and taste-makers in this country. More recently, scholars have sought to recover these voices and aesthetics through revisionary projects, such as the Editing Modernism in Canada project or the Canada’s Early Women Writers project led by Dr. Carol Gerson at Simon Fraser University. It will take some time before the study and appreciation of this work reaches the Canadian public more broadly,” she says.

However, Hall feels that Leveridge’s contemporaries clearly respected her work and held it in the highest regard, noting she was widely anthologized in her time, having been included in John Garvin’s Canadian Poems of the Great War (1918), and Bliss Carman and Lorne Pierce’s Our Canadian Literature (1934), among other collections.

“Moreover, Heather Murray notes in her essay “The Canadian Readers Meet: The Canadian Literature Club of Toronto, Donald G. French and the Middlebrow Modernist Reader” that when the Canadian Literature Club’s membership was asked if any Canadian writer had ever produced a classic in the fall of 2017, they included Leveridge’s poem The Law Bringers alongside Gilbert Parker and Charles Mair. Time unfortunately, has not been kind to Leveridge’s legacy as a poet, and you would be hard-pressed to find one of her poems in a recent anthology or publication,” she says.

Hall says that her favourite poem of Leveridge’s is The Dream Hills which she reveals is a poem about the loss of a loved one and the search for meaning in the face of profound absence and sorrow, like Leveridge’s other poem Over the Hills of Home, about the loss of her brother Frank in the First World War.

“[In both works], the speaker finds nature to be a salve for that pain. [Leveridge] writes;

Your voice is a long-lost music, a murmur upon the wind,And only on memory’s mountain your phantom face I find,But here, ‘mid the shrouding shadows, our kindred spirits meet, On the twilight hills, the dream hills, where thoughts are true and sweet.

The poem is of course, old fashioned for 1920,” she says, “But you have to admire Leveridge’s talent for the classic form, and her ability to engage the reader’s senses through her imagery.