Commentary

Teaching about a legacy of something lasting

November 9, 2017

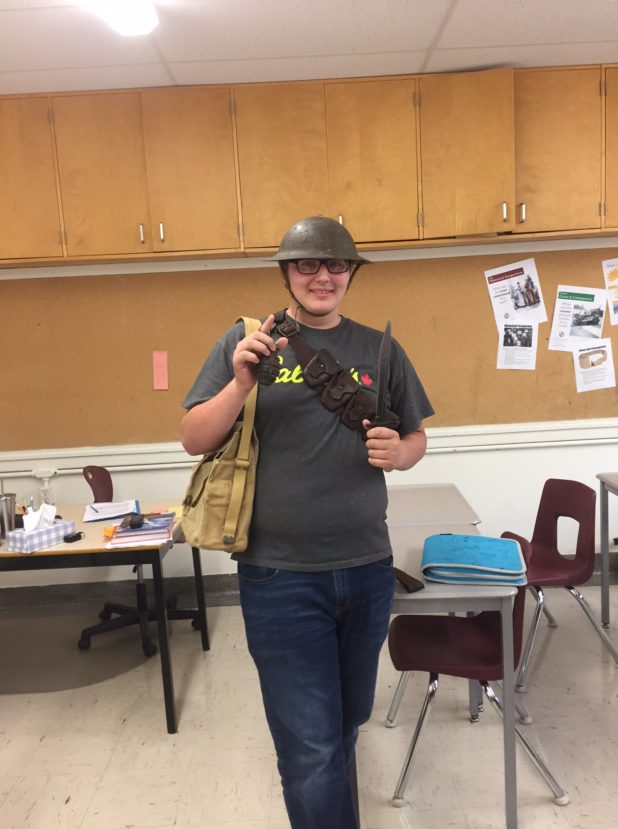

North Hastings High School student Brandon Hall interacts with war artifacts. / SUBMITTED

By Bill Kilpatrick

Both of my great-grandfathers fought in the trenches of the First World War. My grandfather and his three brothers all fought in the Second World War. Another of my grandfathers served at Canadian Forces Base 8 Wing Trenton throughout the Second World War and yet another great-uncle was in the air force. All of them survived, but none of them was the same again. History books will forever have the events of the World War mentioned in them, but not the heroes who fought for their country. Many of them would only remain a glorious light to their families and war heroes to their country, the remainder of their lives. And when they pass, their legacy will live on in their life stories and their obituaries (similar to the ones available on https://www.genealogybank.com/explore/obituaries/all/usa/virginia/danville/danville-register-bee)!

This family history and the stories of what they experienced – both during war time and the difficult reintroduction to civilian life – has compelled me to share these stories with Grade 10 history students at North Hastings High School for more than a decade. One of my goals of sharing these stories, is to bring history to life for them and try to deepen their understanding of what the average solider had to experience in the First World War and afterward.

I read them the words of the First World War soldiers who often describe in gruesome details the realities of trench life. These stories exemplify the dark sense of humour many soldiers were forced to develop.

I present students artifacts that would only be found in a museum – only seen behind glass. I prefer an interactive learning experience where the students get to hold an explore pieces of history.

We explore different coping mechanisms the soldiers used both in and out of the trenches and the often self-destructive coping mechanisms the soldiers used to mask the trauma when they returned home.

“Why is it important to remember these stories?” I’ll ask the youth. “After all, it was over 100 years ago,” I’ll tell them.

This year one of the students responded, “Because it’s shaped the current world we live in and is still impacting us today.”

“Exactly!” I told him. I cannot emphasize enough that the First World War was the most traumatic experience that we as a country have ever gone through. We are still living with its legacy – it’s called generational trauma. This is the true legacy of the First World War.

The youth are always excited to explore and have always been respectful in how they handle the artifacts: they try the helmets on, hold a bayonet, feel the weight of a grenade and the rough ridges of the trench art hammered into the shells and use a stereoscope for the first time. This experience brings the students a little bit closer to the soldiers.

Young people often respond with revulsion to hearing the realities the soldiers experienced such as having rats crawl all over them, being constantly bitten by lice, foul odours, rotting bodies, being buried alive and other daily horrors they had to experience. We discuss how effective the propaganda was during the war in terms of hiding the realities of the trenches, the disconnect it created when these soldiers returned home and how unprepared society in general was to deal with the physical and psychological scars caused by the First World War.

The students are surprised that many of the soldiers came to curse words such as heroism, patriotism, and valor. One such soldier was Tommy Burns, a decorated First World War solider, Second World War Canadian Corps Commander in Italy, pioneer peacekeeper, professor and author.

Burns cursed these words because they were used to manipulate the public into signing up for the First World War which was, in essence, a slaughter. In fact, the heroism and valour the soldiers displayed was for their fellow soldiers and not for some notion of patriotism. The soldiers, however, did expect that their government would help and support them as they returned to civilian life. They hoped their sacrifice would result in a better world.

Given that we live in a time where the war drums are being heard once again all over the world, I feel more compelled now than ever to share these stories and impart our civic duty as articulated by a First World War soldier and poet Wilfred Owen, who ended his poem, Smile, Smile, Smile, with three ominous lines: “Peace would do wrong to our undying dead, The sons we offered might regret they died, If we got nothing lasting in their Stead.”

I believe that the something “lasting” Owen was referring to was peace, because when we forget that the worst peace will always be better than the greatest war, we risk “doing wrong to the undying dead” and dishonouring our veterans. They sacrificed themselves to protect us from ever having to experience what they did. We owe it to them to not repeat the First World War. We owe it to them to maintain peace. My hope is that the youth come away from my lecture with serious skepticism of war because as the military historian John Keegan, points out in his book Face of Battle, “….most wars are begun for reasons which have nothing to do with justice, have results quite different from those proclaimed as their objects, if indeed they have any clear cut result at all, and visit during their course a great deal of suffering on the innocent.” The preamble to the United Nations refers to its sole purpose to “save succeeding generations from the scourge of war, that twice in our lifetimes has brought untold sorrow to mankind” and this is what we must remember: war is a scourge, it is meant to destroy, that is its sole purpose, and if we do not learn to love peace and despise war then we all risk suffering the scourge of war once again. This is the duty of each generation. We owe this to the undying dead.

This is why we need to remember.